Written By Emina Frljak

Introduction

The legacies of war in Bosnia and Herzegovina remain deeply embedded in the social, political, and emotional fabric of the country. Nearly three decades after the 1990s conflict, the echoes of violence continue to shape interethnic relations, community life, and personal identities. Among those affected are war veteran individuals whose lives embody both the scars of war and the potential for reconciliation. Their stories reveal how personal suffering, when met with empathy and structure, can become a foundation for peacebuilding.

The program Konstruktivna upotreba veteranskog iskustva (KUVI), “Constructive Usage of War Veteran Experience”, offers a promising model of this transformation. Implemented by the organization Pravi požar from Derventa, which gathers war veterans and their families, KUVI creates safe and facilitated spaces for dialogue between veterans and young people across Bosnia and Herzegovina. Its main goals are preventing violence, reducing stereotypes, and fostering societal reconciliation by transforming painful war experiences into lessons for peace.

This essay reflects on the KUVI program and its methodology, explores my personal engagement and encounters with veterans, and discusses both the challenges and the transformative potential such initiatives hold for intergenerational healing. It also envisions a future in which the legacy of war is not inherited as trauma, but as wisdom for building a peaceful society.

KUVI Program and Methodology

KUVI was created with the conviction that the experiences of former soldiers can serve as powerful tools for peace education. A key aim of the program is to confront romanticized portrayals of war by offering authentic and unfiltered testimonies from those who lived through it (Grbešić, 2014). Veterans participating in KUVI speak candidly about the physical, emotional, and moral devastation they experienced, portraying war not as heroism, but as destruction.

Through structured dialogue, KUVI creates opportunities for young people to engage directly with veterans. These encounters are carefully facilitated to balance safety and openness. Sessions typically last around three hours, beginning with veterans’ personal accounts, followed by an interactive phase where youth participants pose questions that range from practical (“Where were you during the war?”) to deeply ethical (“How do you talk to your children about peace and friendship with those who were once seen as enemies?”) (Grbešić, 2014).

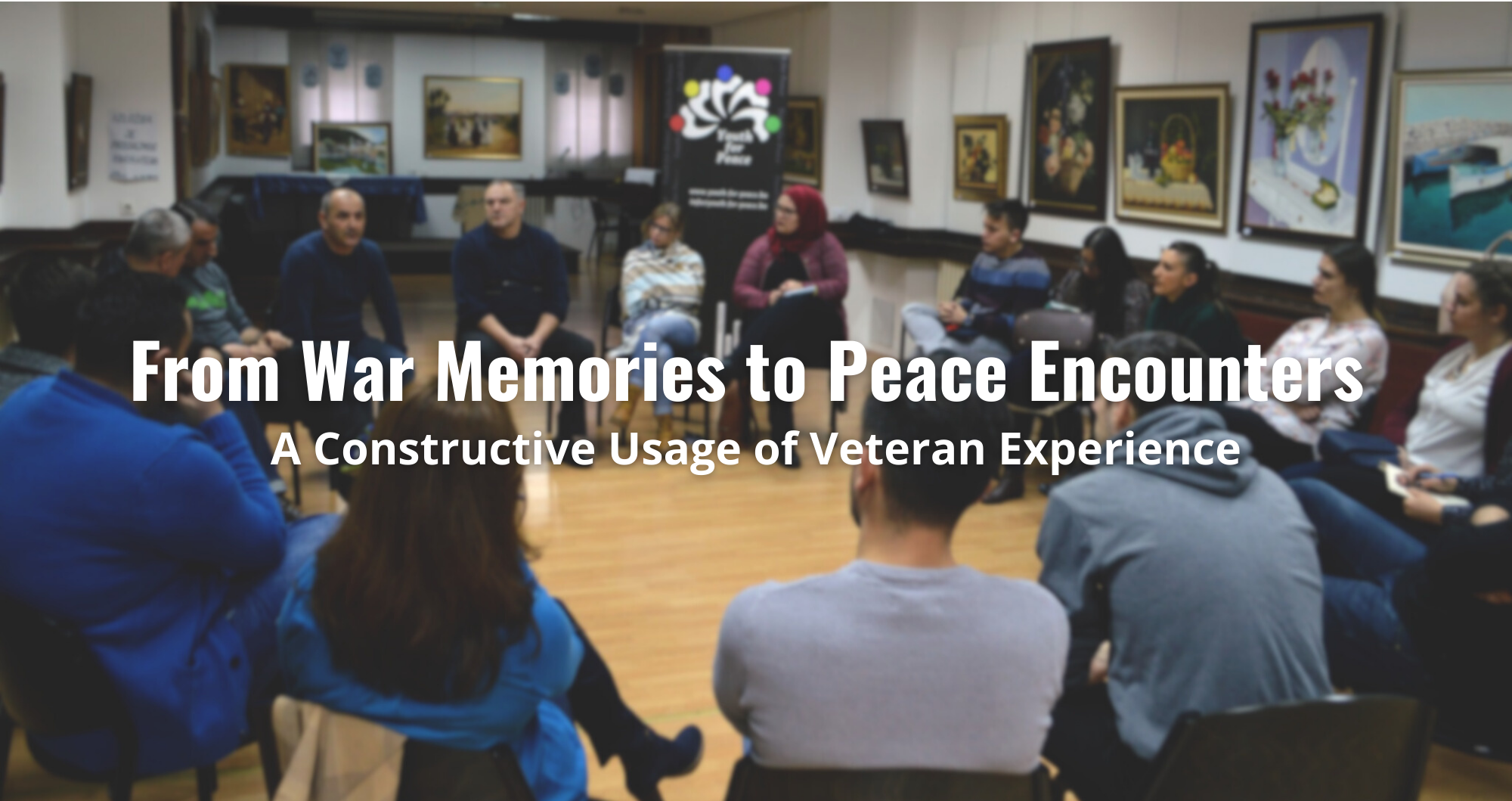

KUVI Session | Photo credit: Youth for Peace

For many young people, this dialogue opens a window into understanding the long-term effects of trauma. They often recognize in veterans’ stories echoes of their own family experiences—emotional distance, sudden mood shifts, or unspoken pain. Through such exchanges, the program not only dismantles stereotypes but also reveals how war’s consequences transcend generations (PAX, 2020).

The work of Pravi požar is particularly meaningful because it bridges individual and collective recovery. The organization provides psychosocial support and structured facilitation for veterans and their families, ensuring that storytelling does not become retraumatizing but instead contributes to healing. This model exemplifies how trauma can be addressed through guided dialogue that empowers participants to reclaim agency over their narratives.

Ultimately, KUVI demonstrates that confronting painful memories can foster empathy and responsibility in younger generations. When veterans become educators rather than symbols of division, they help build a social environment in which peace is seen not as the absence of conflict but as the presence of understanding.

Personal Reflection: From Memories to Encounters

My involvement in KUVI was both professionally significant and deeply personal. First, I participated as a young person and listened to the veterans and then as a peace educator and facilitator, working with groups of young people who were meeting veterans from the three different armies that fought during the Bosnian war. These were not easy conversations. The veterans’ stories were raw, filled with loss, grief, and reflection on moral choices made under extreme circumstances. Listening to them required emotional endurance.

Many veterans spoke openly about their pain and remorse, acknowledging how the war had cost them not only friends and family but also parts of their identity. For them, participating in KUVI was a way of breaking their silence and reclaiming their humanity after years of social stigma and self-isolation.

“When veterans become educators rather than symbols of division, they help build a social environment in which peace is seen not as the absence of conflict but as the presence of understanding.”

As someone who grew up in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the war, my engagement in such dialogue carries a personal weight. I was sixteen months old when the war began and five years old when it ended. My memories of that time are fragmented, like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle where some parts are missing but others remain vividly clear. I remember the terrifying sound of shrapnel hitting our house while my sister and I were alone in a room, the trembling of the walls, and the uncertainty of whether our parents were safe. Yet, alongside those memories of fear, I also remember warmth, sharing food in basements and shelters, neighbours helping each other, and the quiet moments of humanity that persisted amidst chaos.

After the war, I grew up in a monoethnic community, where the idea of ever sitting in a room with those from what we once called enemy armies felt unimaginable. Years later, through my participation in KUVI, I found myself doing exactly that: listening to their stories. That experience taught me to listen not only to narratives that affirm my own understanding, but also to those that challenge it, to hear the pain and humanity behind the stories of others. I began to see the war not just as a series of dates, reports, and statistics, but as a deeply human experience marked by shared suffering and loss. Perhaps the most difficult part was recognizing former soldiers as human beings, capable of both harm and healing. Yet this struggle is a reminder of how deeply dehumanization can take root and how vital it is to keep working toward empathy and understanding, even when it feels uncomfortable.

Challenges and Opportunities

Despite its inspiring model, KUVI operates within a challenging social context. Veterans continue to face stigma, often being viewed through politicized lenses, not as individuals, but as representatives of a single ethnic narrative. This highlights one of KUVI’s challenges: many people in our society still perceive former soldiers from opposing sides through the lens of enmity.

Some of the veterans also struggle with economic insecurity and unhealed psychological trauma. Participation in dialogue can reopen painful wounds, which is why professional facilitation and psychosocial support remain essential components of the program.

Moreover, resistance from political actors who oppose inclusive remembrance practices poses ongoing obstacles. Efforts to create spaces for shared reflection are sometimes dismissed as attempts to “equalize guilt,” which can discourage broader community participation.

Yet, these very challenges underscore why programs like KUVI are so vital: they humanize the experiences of those involved in war and challenge the narratives that sustain division. As highlighted by the Center for War Trauma, such dialogue supports both psychological reconciliation for veterans and the cultivation of critical reflection among youth, encouraging exploration of nonviolent responses to conflict (Pekmez, 2020). KUVI thus provides a model not only for post-conflict societies but for any context where former enemies must learn to live together again.

Reimagining the Future: Learning Across Generations

Looking toward the future, initiatives like KUVI invite us to imagine what peace might look like when built on empathy, and shared humanity. The program reveals that reconciliation is not a single event but a continuous process of learning between generations, across differences, and within ourselves.

Intergenerational dialogue can serve as a bridge between memory and vision. Veterans offer lived truths about the cost of violence, while young people bring hope and creativity to reimagine what peaceful living together can be. The safe, facilitated spaces that KUVI creates are not only sites of remembrance but laboratories of transformation where trauma can be reframed as wisdom and where understanding replaces fear.

“Intergenerational dialogue can serve as a bridge between memory and vision. Veterans offer lived truths about the cost of violence, while young people bring hope and creativity to reimagine what peaceful living together can be.”

For Bosnia and Herzegovina, the challenge now is to institutionalize such practices, integrating them into educational and community frameworks. Programs like KUVI and organizations such as Pravi požar demonstrate that even societies marked by deep wounds can cultivate resilience and empathy. If supported and expanded, these models could help ensure that the next generation inherits not only the memory of war but the tools to prevent its recurrence.

Conclusion

The Constructive Usage of War Veteran Experience program exemplifies how even the most painful human experiences can become resources for learning, empathy, and reconciliation. By transforming the voices of veterans into educational and dialogical instruments, KUVI bridges generations and communities long separated by trauma.

For me, engaging with veterans was not only an act of listening but an act of remembrance, a way to honour my own fragmented childhood memories by contributing to a more peaceful future. I believe that every dialogue, every story told and heard, is a small act of rebuilding trust. If we continue creating spaces where people can speak honestly about the past and imagine new ways of living together, then perhaps the children born today in Bosnia and Herzegovina will grow up without the sounds of fear I once knew and with the sounds of peace that we are all, together, still learning to make.

References

Grbešić, A. (2014, June 22). Konstruktivna upotreba veteranskog iskustva. Radio Slobodna Evropa. https://www.slobodnaevropa.org/a/konstruktivna-upotreba-veteranskog-iskustva/25431332.html

Pekmez, I. (2020, October 20). Centar za ratnu traumu: Ratnim veteranima pomažemo da budu u miru sa sobom. Klix.ba. https://www.klix.ba/vijesti/bih/centar-za-ratnu-traumu-ratnim-veteranima-pomazemo-da-budu-u-miru-sa-sobom/201020117

PAX. (2016). Mapping inclusive memory initiatives in the Western Balkans. PAX. https://paxforpeace.nl/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/import/import/pax-report-mapping-inclusive-memory-initiatives-in-the-western-balkans.pdf

Issue 03 | Reimagining a New Generation of Peace

-

No Planet, No Peace: Reimagining Peacebuilding through Planetary Stewardship

-

When the Earth Shook, Faith Held Us Together

-

Reimagining Peace through Rumi’s Lenses: A Voyage into Poetic Wisdom, Politics, Diplomacy, and the Transcendental

-

An Alternative Peacebuilding Vision in a Post-Liberal Era

-

Sing My Soul

-

Reimagining a New Generation of Peace with Servant Leadership and Nonviolent Communication

-

Threading the Future: Mentoring the Next Generation of Peacebuilders

-

If We Can Teach AI to Practise Empathy: Nonflict and a Generation of Peacemakers

-

Peace Leader Spotlight | From Grandmother’s Legacy to Global Peacebuilding: Issah Toha Shamsoo

-

Young Leaders for Peace: Meeting the Moment through Youth Peace Leadership Development at the University for Peace

-

Reimagining Peace Through Young Voices in India: Spotlight on Women Journalists and Their Stories

-

Peace Dwelling and Belonging: Stan Amaladas on rethinking what it means to live well with each other

-

Pockets and Peace Design: A collaborative design framework to advance health equity and build peace

-

From Shrinking Spaces to Shared Strategies: Insights from Central Asia on how to build collective action for conflict prevention and peacebuilding

-

From War Memories to Peace Encounters: Constructive Usage of Veteran Experience

-

Call for Submissions | Issue 04